I recently mentioned Sir John Falstaff, as one of my favorite Shakespearean characters. The man was utterly disreputable: a drunk, a coward, a lecher, a glutton, utterly without redeeming qualities—what’s not to love about him? Clearly, Shakespeare loved him; Falstaff appears in four plays and is mentioned in another.

Supposedly, the character was based on Sir John Oldcastle. There is even a book, published in 1600—The True and Honorable Historie of Sir John Oldcastle, the Good Lord Cobham—allegedly written by Shakespeare; but it is widely discredited.

Falstaff is seen, in his purest form, in Henry IV, Part One. Young Hal loves the old man despite the urgings of The Chief Justice, a stick-in-the-mud who cares only about the responsibilities that the young prince is ignoring. The Chief Justice had come to power because he helped the prince’s father—Henry Bolingbroke—usurp the throne of Richard II, in order to become King Henry IV.

I first saw the play in high school, when we took a class trip to Stratford, Connecticut where Shakespeare’s plays were regularly performed in a manner consistent with the Bard’s times. It was an American version of the tourist-attracting Globe Theater in London. I was young and completely ignorant of the historical elements of the play, but Falstaff’s qualities—or the lack thereof—were readily apparent. His bawdy punning did not escape my adolescent attention either.

Many years later, I found a delicious little book—Shakespeare’s Bawdy, by etymologist Eric Partridge—that explained many of Sir John’s jokes that had gone over, or under, my teen-aged radar back in Connecticut. Normally, I avoid explanations of humor because—as E.B. White warned, “Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better, but the frog dies in the process.” However, Shakespeare’s humor is often based on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century slang—so a little explication is appreciated.

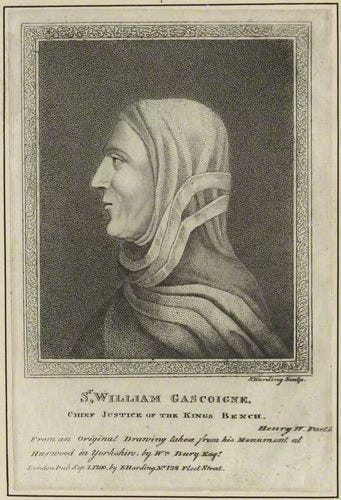

Still more years later, I began to study genealogy. I was able to trace my lineage way back, much further back than Shakespeare’s time. One of the ancestors I discovered was Sir William Gascoigne (ca. 1350-1419), Lord Chief Justice Under King Henry IV. He was my fifteenth-great-grandfather on my father’s side. He was also the model for Shakespeare’s Chief Justice (who is not named in the plays). While it’s fun to think that I have an ancestor depicted by The Bard of Avon, it’s unsettling to know that his guidance of the future King Henry V was responsible for the downfall of Falstaff.

Falstaff’s death—supposedly due to a fever brought on by Henry V’s abandonment of the boyhood friend, what we would call a broken heart—was reported in Henry V. By then the dissolute young prince had become the hero of Agincourt. Sir William Gascoigne’s lessons had made a king, but unmade one of Shakespeare’s most beloved characters.

By the way, Shakespeare’s “histories” are not history as we think of it. The Bard altered facts to serve the stage. For example, in Julius Caesar, the tyrant was assassinated in The Forum, when the deed was actually committed in the Curia di Pompeo, Largo di Torre Argentina, halfway to the Pantheon. Never let the truth get in the way of a good story. In Henry IV, Part Two, the young prince kills the rebel Harry Hotspur. Hotspur did, indeed, fall at the Battle of Shrewsbury, but no one knows how. Because he was a rebel, his head was exhibited on a pike, and his body quartered, and widely dispersed. It was later reassembled and buried in York Minster.

We have visited York Minster, but did not see Hotspur’s gravesite. That’s disappointing—now—since newer genealogical research revealed that Harry Hotspur was my sixteenth-great-grandfather on my mother’s side.

Sir John Falstaff may never have existed, outside of Shakespeare’s imagination, but—if he had—a couple of my ancestors would have known him.

Paid subscribers to these substack pages get access to a complete edition of my novella: Noirvella is a modern story of revenge, told in the style of film noir. They can also read the first part of Unbelievable, a kind of rom-com that forms around a pompous guy who is conceited, misinformed, and undeservedly successful. Both books are sold by Amazon, but paid subscribers get them for free!

Also, substack pages (older than eight months) automatically slip behind a paywall—so only paid subscribers can read them. If you’re interested in reading any of them, you can subscribe, or buy them in book form (I’ve released two volumes of Substack Lightnin’ on Amazon).

Meanwhile, it is easy to become a paying subscriber (just like supporting your favorite NPR station). It’s entirely optional, and—even if you choose not to do so—you’ll continue to get my regular substack posts—and I’ll still be happy to have you as a reader.

Agreed... Hotspur had been part of Bolingbroke's rise to power, but turned against him later.

Also, Shakespeare makes Hal and Hotspur contemporaries, but I believe the real Hotspur was close to a contemporary of Henry Bolingbroke.

Henry IV, Part I, is my favorite Shakespeare play.