“Never Meet Your Heroes. They'll Surely Disappoint.”

Marcel Proust is among the people alleged to have been first to say that—but “alleged” covers a lot of ground. More to the point: not many people take that advice when given a chance to test it. Besides, how many people learn anything from the experiences of others?

Mostly, we learn, with difficulty, and only in response to (our own) pain.

I’m still working on Meetings with Remarkable Men ...and a Few Others (at least when not distracted by other writing temptations). I half fear that the “Proust” quote will be more relevant to that new book than I’ve envisioned.

By the way, the excerpt, below, mentions a few people who are likely to get chapters their own, eventually. We’ll see.

Or maybe we won’t.

Wading with Heraclitus

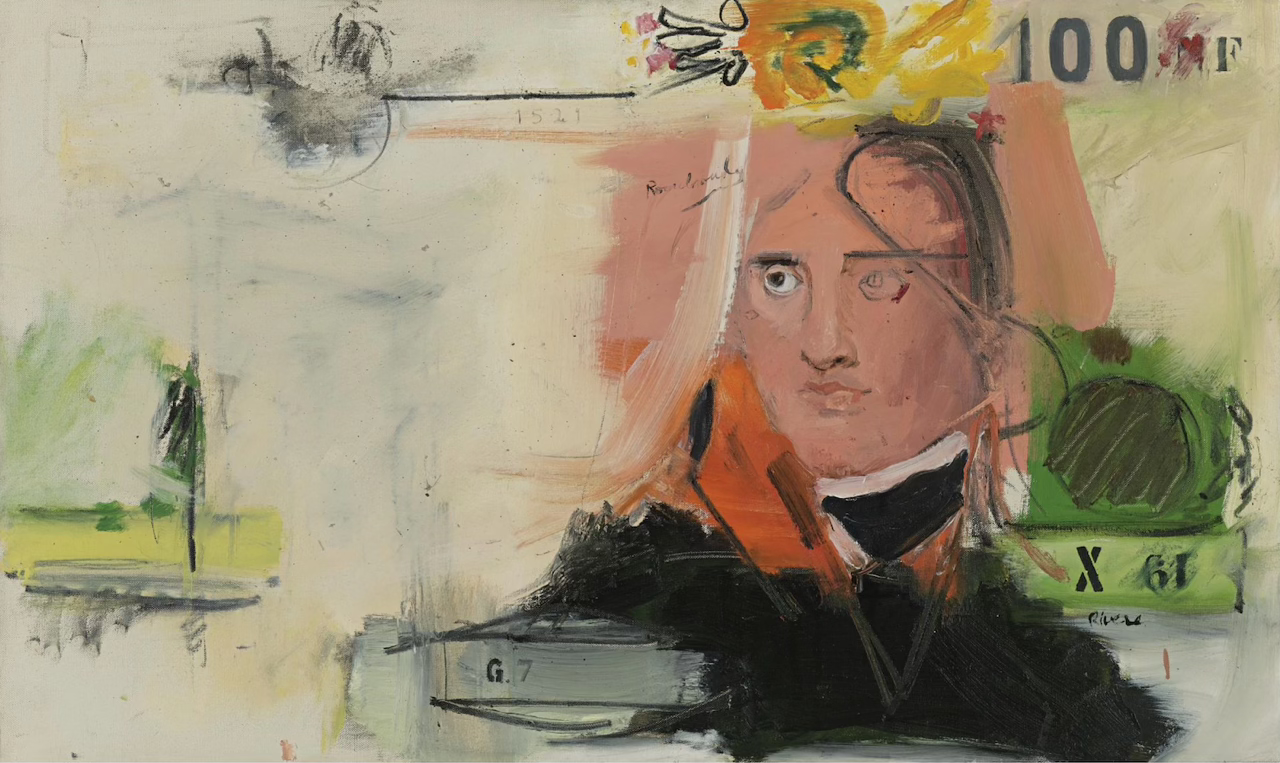

Larry Rivers, Little French Money, 1962

When I was still in high school, I discovered the paintings of Larry Rivers. Like some of his contemporaries (Bob Rauschenberg, for example), his work bridged the gap between the end of Abstract Expressionism and the early days of Pop Art. It was a heady mix, as thrilling and promising as my own adolescent art career.

I felt a real connection to his work.

Within a few short years, my early infatuation with Abstract Expressionism began to cool (although I don’t think I ever outgrew the compositional lessons I learned there). The Pop Art movement had moved on to more conceptual forms that bridged dance, theater, painting, sculpture, and virtually anything else an artist might want to toss into the mix. There had been teachers who told me that my interest in science was incompatible with my “artistic” side—but the art world was beginning to appreciate science and technology—something that seemed incomprehensible for those who subscribed to earlier, more romantic, notions of (capital A) Art.

The climax of that transition was the formation of EAT—Experiments in Art and Technology. That organization grew out of a remarkable event in the Fall of 1966: Nine Evenings: Theater and Engineering. It was an extended Happening—in which artists and technologists collaborated on projects that had never even been imagined, let alone attempted, before. I saw works performed by everyone from composers John Cage and David Tudor, dancers Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, and Yvonne Rainer, multimedia artist Öyvind Fahlström, painter Alex Hay and his wife, dancer Debbie Hay, my mentor—printmaker Bob Schuler—who performed with painter Bob Rauschenberg, and mixed-media artist Robert Whitman. It was organized by Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver (an engineer from Bell Labs).

After the Nine Evenings, they created EAT so that artists could connect with engineers to solve technical problems that neither could ever encounter independently.

EAT was made for me; I joined immediately.

At the time, I’d been working on a series of paintings that used mathematic progressions to generate their design (the idea was that, by using a formula, I could eliminate my personal influence on the patterns that formed). It was an attempt to make art that was purely impersonal, devoid of romantic or idiosyncratic preconceptions.

Of course, the very act of choosing to delegate design choices to an impersonal algorithm inadvertently revealed even more about the person I was trying to hide.

We can never really eliminate ourselves from what we create.

One of the methods I used was based on prime numbers. One night, my kitchen was filled with engineers from EAT, and I showed them my working notes/sketches. When I mentioned prime numbers, one of them asked, “There can’t be very many prime numbers, can there?” They were shocked when I replied, “168 in the first thousand whole numbers.”

There are more kinds of nerds than were dreamed of in their philosophy.

Another night, EAT organized a kind of mixer for artists and engineers in a storefront on NYC’s Lower East Side. The room was packed with well-known artists I never imagined I might meet. At one point, I was speaking with a Bell Labs scientist who had been designing new fabrics on a computer. Remember, this was the sixties—there were no personal computers, yet, and artists had not yet dreamed of using them. Someone shoved from behind me—and I turned just in time to be face-to-face with Larry Rivers, who promptly elbowed me aside to get to the engineer with whom I’d been speaking.

It was a case of shock-and-awe. Well, mostly shock. I looked around the room for any kind of support.

About three feet away, Ornette Colman stood, silently shaking his head in disbelief. In retrospect, I understand that musicians work in cooperation with other musicians, and he must have been mystified by the egotistical antics of visual artists en masse.

I looked away, and made eye contact with Tom Gormley, another artist I knew through Bob Schuler. He also shook his head, sadly, and muttered four words that still ring true, nearly six decades later.

“Artists are such pigs.”

I have not been able to see Larry Rivers’ work the way I had before that night. Heraclitus wrote, “No man ever steps in the same river twice. For it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” Nor can any of us look at the same paintings twice.

Paid subscribers to these substack pages get access to a complete edition of my novella: Noirvella is a modern story of revenge, told in the style of film noir. They can also read the first part of Unbelievable, a kind of rom-com that forms around a pompous guy who is conceited, misinformed, and undeservedly successful. Both books are sold by Amazon, but paid subscribers get them for free!

Also, substack pages (older than eight months) automatically slip behind a paywall—so only paid subscribers can read them. If you’re interested in reading any of them, you can subscribe, or buy them in book form (I’ve released two volumes of Substack Lightnin’ on Amazon).

Meanwhile, it is easy to become a paying subscriber (just like supporting your favorite NPR station). It’s entirely optional, and—even if you choose not to do so—you’ll continue to get my regular substack posts—and I’ll still be happy to have you as a reader.