Playing the Part

I’ve decided that my book-in-progress (Meetings with Remarkable Men

...and a Few Others) should include other influential personae—beyond the ones I’ve actually met. Many of the most influential folks existed only in print—so in they go!

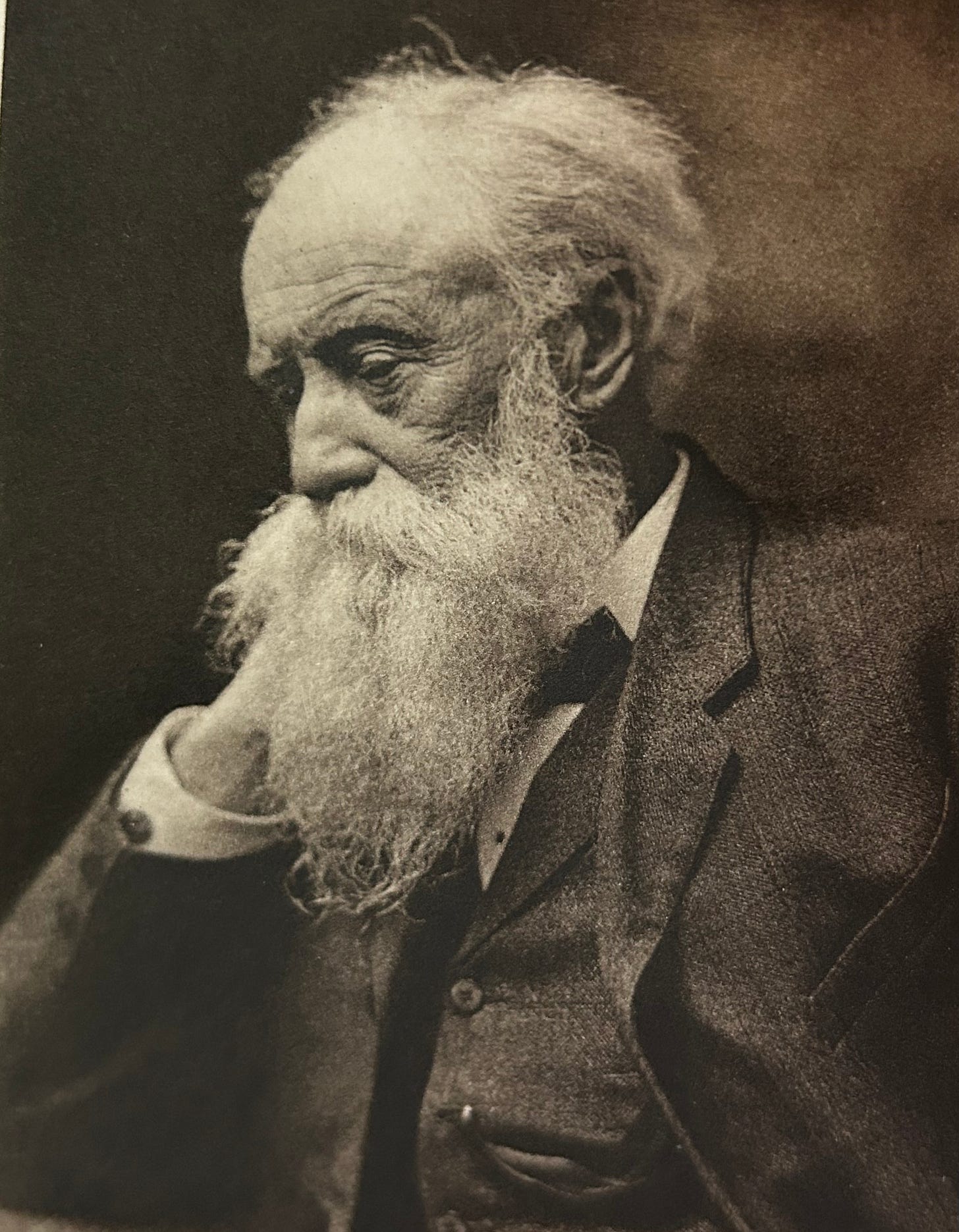

Today’s addition is someone I would dearly have wished to meet—but he died almost two decades before I was born. I do have most of his twenty-odd books (I think I’m missing just two of them). I do, sometimes, write about the subjects he wrote about, and often drive past the house where he lived, in West Park, NY (and have visited Woodchuck Lodge, the summer house built on land where he was born—and where he is buried). The last time I was at the gravesite, someone asked if I was an actor playing him for tourists.

I’ll admit, there is a slight resemblance…

Rôle Model, in absentia

Some fifty years ago, I abandoned the kind of art that might have led to a career of galleries and exhibitions. Instead, I began to make art that was more in line with some of my other interests—specifically, in science and nature. I started looking intently at things that had previously only caught my eye at a superficial level.

I started making botanical pencil drawings of the wild flowers that grew in Ulster County. The process was fascinating, for me, as they required me to observe their minute details, and concentrate on careful draftsmanship (something I had ignored when I thought I was making “serious” art).

I had managed to find a form of art that was profoundly out-of-fashion.

Around the same time, I noticed a historical road sign in High Falls: “John Burroughs taught school here.” I had no idea who Burroughs was, or why his employment was noteworthy.

Curiosity led me to discover that Burroughs had once been one of the most popular nature writers of his day. I found some of his writings, and learned that he and I had walked many of the same trails, fished the same streams, and been enchanted by the same natural world.

We were both, for the most part, autodidacts. He never got past the eighth grade (apparently, that was enough, back then, for a teaching job)—he had walked the sixty-odd miles from his home in Roxbury to the little schoolhouse near the D&H Canal—and I was a college dropout.

We had educated ourselves with serious reading. We had both been influenced by the essays of Emerson—and taken them to heart. Burroughs amused me by responding to Emerson’s “hitch your wagon to a star” by writing, “We are prone to hitch our wagon to a star in a way, or in a spirit, that does not sanctify the wagon, but debases the star.”

One of his favorite places, The Peekamoose—headwaters of Rondout Creek—was also a favorite of mine; I have fished and photographed it countless times. He wrote, “If I were a trout, I should ascend every stream till I found the Rondout. It is the ideal brook. What homes these trout have, what retreats under the rocks, what paved or flagged courts... what crystal depths where no net or snare can reach them.”

I read everything of his that I could find.

I learned that he had built a cabin, for use as his study, less than ten miles from where I lived at the time. I immediately drove to Slabsides, in West Park—not far from Black Creek, where he once hiked with Walt Whitman, a stream where I had fished for trout and herring.

Unfortunately, Slabsides was closed to visitors.

I left a note, saying I was working on a book project (tracing the history of Rondout Creek, from its source to its mouth on the Hudson) and would like to pay my respects to the man who had so loved The Peekamoose.

A week later, I got a call telling me when I should come back. I don’t know who I expected to meet, but it certainly wasn’t a heavyset woman in her seventies, wearing a loose-fitting house dress—maybe a park ranger, but not her.

She introduced herself as Clara Barrus—John Burroughs’ granddaughter. We sat and talked for an hour or two, inside the cabin her grandfather had built for himself, on benches he had made, from trees he had cut down, next to the desk he had fashioned from bent trigs—a desk that still held specimens of rocks, and leaves, and feathers, and a turtle shell, that he had collected.

At the end of my visit, she said that it was time for her daily swim—in the Hudson.

Just before parting, she told me that Henry Ford had given her grandfather a Model T, and that he loved driving it—but that he terrified his passengers. He was always looking at birds and animals, while he drove, while wildly waving both arms in their direction.

I do much the same, today, often producing the same terror in my passengers—especially when done at Thruway speeds—pointing out the broad-winged hawks hunting from tree tops, or swooping down to snatch the errant mouse from grassy shoulders of the road.

Paid subscribers to these substack pages get access to complete editions of two of my novellas. Noirvella is a modern story of revenge, told in the style of film noir. Unbelievable is a kind of rom-com that forms around a pompous guy who is conceited, misinformed, and undeservedly successful. Both books are sold by Amazon, but paid subscribers get to read them for free. Also, substack pages (older than eight months) automatically slip behind a paywall—where only paid subscribers can read them. If you’re interested in reading any of them, you can subscribe (giving you free access to them), or buy them in book form should you prefer the feel of a physical book. Meanwhile, it is easy to become a paying subscriber (just like supporting your favorite NPR station). It’s entirely optional, and—even if you choose not to do so—you’ll still get my regular substack posts—and I’ll still be happy to have you as a reader.

Thanks, Lisa... and, about those"kindred spirits": reading allows us to meet with them regularly, even if they've been dead for a thousand years. That's why I'm including some of them in this book-in-progress.

As for Burroughs, I suspect I'll be writing more about him soon.

I believe we all have a muse (or muses) that are our kindred spirits. It's hard to even put into words (you did an admirable job here) the way it can make us feel. The outward expression of wordsmithing becomes all the richer if we're lucky enough to discover these connections--just the glossy part we can share with others. The deeper emotion of those personal connections needs to be savored. Thank you for sharing--Burroughs is a worthy addition to what you're writing.