What We Know of Life, We Learned from Death

I apologize for writing, once again, about recent medical traumas endured by our little family. It’s a running joke that folks of a certain age, when they get together, spend most of their time discussing their medical issues—so much so that one wag described our conversations as “organ recitals.”

I’ll try to steer clear of that.

Let’s just say that my wife and I have spent a lot of time, lately, in the company of doctors and their legions of support staff. And their technologies—and that last item is the inspiration and reason for this post.

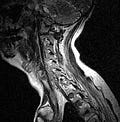

The other day, I finally learned that I will not be needing surgery for the injury to my neck. I will have to continue wearing a neck brace (that I’ve taken to calling my “cone of shame,” a term that most dog owners might recognize). During that visit, I got to look at x-rays and MRIs of my cervical spine. Right there, in the front of my spine, between vertebrae C3 and C4, a gaping break that looked like the cruel grin of an ancient skull’s dangling mandible. The neck brace is meant to prevent that break from opening further.

The break doesn’t show in this MRI, but I got to see part of my own brain,

something I never expected to see.

Most of us don’t think much about the fact that we have nightmares—scary skeletons—walking around inside us. Unless something happens to remind us. I was not scared (at least once I knew that there was little chance of dying or spending the remainder of my life as a quadriplegic).

Mostly, I was fascinated.

I recall, many years ago, when I had abdominal surgery, under local anesthetic. I asked the surgeon and his assorted assistants if there was any way a mirror could be set up—so that I could watch the procedure. After all, how often do we have a chance to see the inside of our own bodies?

What I got was, “No.”

Their response was so emphatic, that I suspected that I had rudely asked to learn the secrets of their priesthood; that my question struck them as deeply sacrilegious or downright blasphemous.

No doubt the real reason for their denial was nothing more than a hospital rule. It had probably been created by a different set of high priests (the hospital’s lawyers). The experience reminded me of the very first piece of my writing for which I received payment. It was a book review of Richard Seltzer’s Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery, and it was published in 1977 by East-West magazine.

I no longer have a copy of that magazine, but I have been able to reconstruct the review from my notes, kept at the time. It’s curious that some of the issues raised in the article still intrigue me—and that the tone of the writing was not very different from that of my other non-fiction, written nearly half a century later.

Book Review

One of the jacket blurbs (an excerpt from a pre-publication review by Tom Wolfe) describes Richard Seltzer’s Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery as “Gray’s Anatomy, Vol. II.” As usual, Wolfe’s hyperbole catches the eye, but just misses the truth. It is true that Seltzer discusses anatomy at length, but there the resemblance stops. Where Gray’s is an encyclopedic compendium of facts, Mortal Lessons is all questioning and insight. We are reminded of Mark Twain’s comment, “I can say right now that Kipling and I are two most remarkable men—he knows all that can be known, and I know the rest.”

That is a paraphrase of Twain’s words, but the spirit of the thing is accurate, “The rest” is the better part of knowledge. While it is possible to be enamored of facts alone (indeed, the history of Western science is one long gluttony of facts), it is still the awe of nature that nurtures and impels us. Modern medicine would have us believe that their craft is purely technical, devoid of the magic and mystery on which ancient medicine was founded. Anyone who has studied evolution, be it biological or intellectual evolution, knows that one never completely escapes one’s ancestry.

The past lives in us.

But Seltzer is no mere atavism. His acknowledgment of the existence of miracles is not a confession of weakness on his part, but a critique of the self-imposed poverty of surgery itself. Beyond admitting a fear and trembling before the face of the unknown, Seltzer’s humility is a positive virtue. He represents the antithesis of hubris, the sin of excessive pride. Hubris was the single sin which unfailingly invoked the wrath of the Greek gods. It reins in the very swagger of the high priests of technology (Medicine being only one order among many in thos most Western of religions). Seltzer’s respect for nature—shall we call it the Cosmos?—verges on the transcendentalism of Thoreau. Indeed, the tone (at least of the first half of the book) is reminiscent of that chapter in Walden entitled, “Where I Lived, and What I Lived for.” Perhaps a better comparison could be made with the works of Loren Eiseley. Both men are concerned with bones, and the mystery of time and life—and that greatest of metaphysical mysteries, death.

The earliest impulse of our own priest-physicians was to open the body and peer at what lay hidden there, at first with religious awe, and later with true objective curiosity… the very word abdomen is an archaic term whose exact origin cannot be found, but which is thought to come from the ancient Greek word for hidden or occult.

Medicine, as we know it, did not simply appear (fully-armed, as Athena from the head of Zeus) but slowly evolved from earlier means of confronting the mysteries of life, death, and disease. Magic served the same function for our ancestors. Most physicians would have us believe that we have left all that hocus-pocus behind us, but we obviously have not. The assumptions that serve as the foundation of our sciences are quite different from those that formed the basis for the occult or mystical systems of their world. A moment’s honest reflection, however, must reveal that both approaches are ultimately dependent on assumptions that cannot be proven or justified by logic alone.

In short, science and religion (the modern descendants of ancient magic) are elaborate structures based on articles of faith.

When our ancestors made sacrifices to their gods, a special priest, called a haruspex, came to examine the entrails. What was ought in the steaming viscera was a portent—a sign to guide men’s actions. It was assumed that the gods would transmit essential information via the inside, the hidden parts of the body. Most of these sacrifices, of course, were of food animals, not humans—but certainly the human interior was as laden with mystery as that of a cow or sheep!

We tend to think of Anatomy as a rather dry subject—all answers and few questions—but how many laymen know what is actually inside them? The subject is likely to send chills through the squeamish, and it should: squeamishness is no more than fear of the unknown. Richard Seltzer, as a surgeon, is not likely to suffer from squeamishness—but the sight and feel of the forbidden recesses of the body inspire in him the same reverence and awe felt by the haruspex.

Seltzer is aware that reverence is not medicine’s only tie with Science’s ancestor, Magic. Ritual is essential (an earlier book by the same author was titled Rituals of Surgery). Empathy, a kind of communion between doctor and patient, seems to be necessary. These attributes may be played down by so-called objective physicians—but what is “a good bedside manner,” if not a kindling of the patient’s faith in the doctor?

One thinks of doctors as being concerned only with life and its preservation, Yet much of Seltzer’s book is devoted to discussions of death. He writes clinically, without hiding the fact that death remains the greatest mystery of life. One realizes, with a shock, that most of doctors’ expertise in life preservation has been gleaned from death—from secrets pried from bodies suspended in tanks in the basement of the Anatomy lab.

Paid subscribers to these substack pages get access to a complete edition of my novella: Noirvella is a modern story of revenge, told in the style of film noir. They can also read the first part of Unbelievable, a kind of rom-com that forms around a pompous guy who is conceited, misinformed, and undeservedly successful. Both books are sold by Amazon, but paid subscribers get them for free!

Also, substack pages (older than eight months) automatically slip behind a paywall—so only paid subscribers can read them. If you’re interested in reading any of them, you can subscribe, or buy them in book form (I’ve released two volumes of Substack Lightnin’ on Amazon).

Meanwhile, it is easy to become a paying subscriber (just like supporting your favorite NPR station). It’s entirely optional, and—even if you choose not to do so—you’ll continue to get my regular substack posts—and I’ll still be happy to have you as a reader.